Eat and carouse with Bacchus, or munch dry bread with Jesus, but don't sit down without one of the gods. — D.H. Lawrence

The English writer Hilaire Belloc wrote, regarding his youth, that he had forgotten the town, forgotten the girl, but the wine was Chambertin. — James Salter

I was up in Sonoma County for lunch when my friend ordered split pea soup and I was overcome by the sterility of it all — the desiccated vines, polished concrete, bodies of paunch and jowl, the unnatural quiet! Then followed a conviction hurled upon me as from a great height: nobody in wine country is having sex.

Recently I am tabulating the reasons to live in San Francisco. There are many, and it’s been easier to start via negativa; for example, San Francisco’s proximity to the world’s greatest wine-producing regions is not a good reason to live here.

We believe wine country is beautiful and it is, but this is mostly a matter of hills: once there are hills, light will take care of the rest. And it is precisely because we believe wine country is beautiful that your first trip to Sonoma is such a shock. It is a dusty and burnt pile of dirt. Almost everything is dead and an enormous fire hazard. Now, it is not a crime to be dusty and if it was nobody would visit Tuscany — no, the great offense in Sonoma is what we’ve done to it.

Fifty years ago, the world — the French — discovered California wine, after which money poured into this sleepy backwater, barely even a region, just a few valleys which by all rights should be a refuge for shepherds and outlaws, or perhaps a movie set for Western films, and the people with money built a lot of hideous tasting rooms, so now everything is bloodless. There is no life, except the grape vines stretching their roots into the powdery soil, and who would call that a life?

This is how a typical tasting goes. First, select a winery and make a reservation. Only members can make reservations, but if you’re not a member it’s easy to join: pay four hundred dollars, and you’ll be mailed a few bottles of wine to be stolen off your front porch. After you’ve made your reservation, drive an hour and a half from San Francisco to the winery. If you cannot afford a designated driver, one will be appointed to you (either the most sober woman or most confident man in your party).

The tasting room resembles a recently renovated airport. There are high ceilings with big windows, shiny concrete floors, and high-top tables with stools. It is very quiet, and so echoey that your fellow tasters huddle around their meager furniture allotments and speak in hushed tones. Children are banned. This should be relaxing, but everyone is carrying tension in their back and shoulders, and you get the impression they’re talking about when to move their parents into a nursing home. It’s all fraught with money and everyone is like you in some unnerving way.

Then the wine arrives. Each glass only contains two sips, but you will get drunk nonetheless. It doesn’t matter how good the wine is — drinking wine is an exercise in classification, something that humans are supremely good at and instinctively enjoy. It is like astrology, in that the scientific explanations are superior but unsatisfying. Lately I have wanted to learn more about wine, in the same way I want to learn more about astrology, which, contrary to expectations, is not to get laid, but to have a broader vocabulary for speaking about life with my friends.

I don’t understand how people collect wine, I drink bottles as soon as they pass into my hands. Collecting is an act of delayed gratification: you buy something that can’t be enjoyed for several years — you must exercise patience until the drinking window opens. That’s another reason people put their wine in caves and cellars: it’s not for the climate, it’s that the easiest way to pass the marshmallow test is by closing your eyes.

After the tasting, the servers bring out a slip of paper, the sort of thing golfers keep score on, and you tick off any bottles you’d like to take home. When I was last in Sonoma I bought a few bottles just to be festive, and presently found myself holding hundreds of dollars of wine that I didn’t particularly like and that I can’t drink until 2026. It all happened so fast. It was just like being robbed in my sleep.

Back to the sex. It’s not only that the buildings are improper to the landscape, the tasting rooms inimical to eroticism. It’s also a problem of lifestyle. A character in Don DeLillo’s White Noise comments, “Mud slides, brush fires, coastal erosion, earthquakes, mass killings, et cetera. We can relax and enjoy these disasters because in our hearts we feel that California deserves what it gets. Californians invented the concept of life-style. This alone warrants their doom.”

This is lifestyle: we spend our days in the sun doing activities that keep us physically busy and mentally occupied, or vice versa, while our consumerist instincts add ever-new tiers to these activities — the latest road bike, a fourth surfboard, some special reservation at a winery — that signal our status and give us a reason to keep showing up to work. Soon we care more about our tennis racket than our game. Soon we care more about what wine we’re drinking than why. For thousands of years, drinking wine has been a libidinous communal experience, or so I imagine, but lifestyle strips all that away.

Maybe I’ve got this all wrong. Perhaps all this money and viticulture elevates wine, purifies it, turns it into an art. In that case, it still feels like your fellow tasters have chosen one pleasure of the body, located on the tongue, over another seated further south. And looking around at the couples sitting in silence, reaching for their glass, one can only conclude that Sonoma remains the promise of a good time once you’ve lost your libido.

One last thing about Sonoma. There’s no privacy, because of all the hills. Everywhere you look is a vista and someone else’s vineyard in it. Out there, somewhere, is an enormous Hispanic population keeping this whole operation running.

When we tear down all the tasting rooms and replace them with goatherd caves and wooden shacks, then we’ll be getting somewhere. Ideally we are drinking wine fearing attack by mountain lions or stagecoach bandits. That’s living. That’s sex.

The first time I visited Sonoma it was pissing rain, and I rather liked it, because you couldn’t see the vines or the wineries, only the mass of mountains and the valleys in the dark. What could I think, when I returned in the daylight, except that all those grapes and all that money have ruined some perfectly good hills.

CONTENT CROP 🌾

Leisure and Liberality || First Things

Why does nothing seem interesting, everything dull and gray? The answer might be not that the world is boring, but that we ourselves are dull, shallow, and malformed.

note: “what is your relationship to boredom?” is a fun question to ask your friends when you’ve run out of things to talk about

Sorting the Self || The Hedgehog Review

The personality assessment regime to which so many eagerly submitted did not just improve management or propel new clinical research lines — it salved an existential wound. By codifying the individual, it shortcut the unexpectedly long haul of internal reconfiguration.

note: Philip Rieff alert

Most people who consult me wish to receive specific, narrow diagnoses, and routinely break down in my office when they do not receive them. For a while I thought that the desperation I saw in reaction to a diagnosis denied was connected to the wish for a quick fix—a medical intervention only accessible with the “right” psychiatric label. It became apparent to me over time, however, that most patients actually desired a diagnosis in order to confirm an identity. Many people I saw had constructed an identity that revolved around their self-diagnosis; they explained large parts of their biography in terms of this psychiatric marker. In these cases, a denial of diagnosis on the grounds of careful psychiatric and psychotherapeutic evaluation proved almost impossible. These patients would often break down in a state of confusion and despair, as if they were no longer able to make sense of their lives because they had been robbed of a precious resource, a signifier that contained their overwhelmingly complex experience.

note: I repeat, Many people I saw had constructed an identity that revolved around their self-diagnosis; they explained large parts of their biography in terms of this psychiatric marker

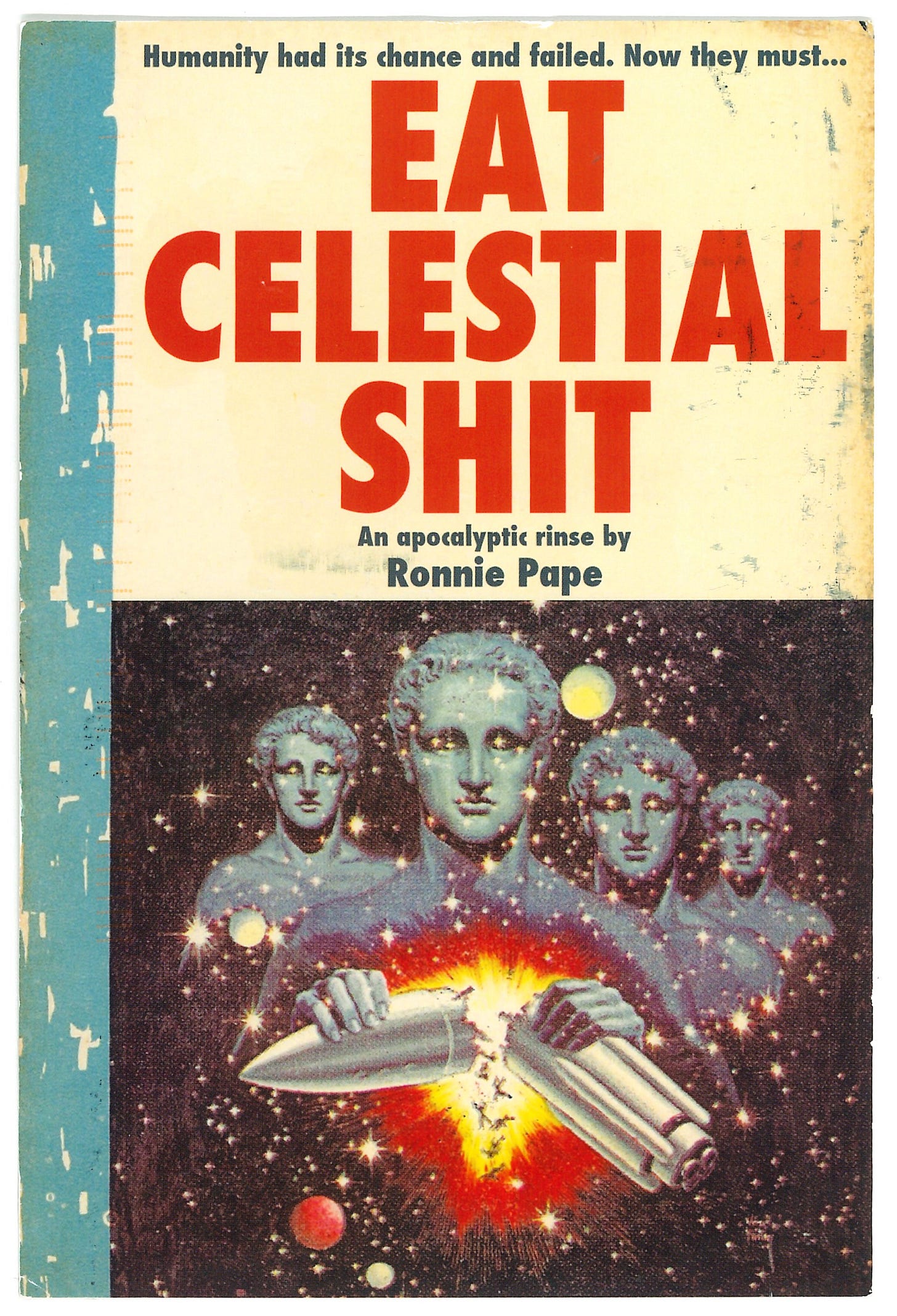

POSTCARDS FROM OUTER SPACE 🎴

THE BOOK BARN 📖

Hard Rain Falling by Don Carpenter

(Fiction, 1966. $15.)

He had read in a paperback mystery the line, “Sex is nice, but there are times when you’d rather cut your throat,” and he knew that feeling. He hated having to induce passion in himself.

note: what an electric thrill to read a book that casually mentions the street you live on, is this why people live in New Gork City?