Once you start a file, Delphine, it’s just a matter of time before the material comes pouring in. Notes, lists, photos, rumors. Every bit and piece and whisper in the world that doesn’t have a life until someone comes along to collect it. It’s all been waiting just for you. — Don DeLillo, Libra

My cousin was married in Pacific Palisades six months ago. My family rented a tranquil house in the hills that has been miraculously spared by the Palisades fire. The rest of the neighborhood is ashes. It was the first Airbnb I’ve stayed in that was a family’s full-time home — I didn’t know where they disappeared to, but I was clearly sleeping in the bedroom of an overzealous eight-year old who’d been given a label-maker and tagged every object in the room, no matter how mundane. DESK. BOOKS. DOOR. HARDER BOOKS. LAMP.

I was relieved to hear the house survived. I spent a lot of time that weekend looking at the family’s pictures on the wall, flipping through photo books on the coffee table. One striking post from the LA fires shows a group of firefighters walking into a burning house, and emerging with their arms full of photo albums. The only other thing we see them save at the end of the clip is a grandfather clock, which, while poignant, is also deeply funny, because what do they expect you to do with a grandfather clock when you’re homeless. It’s a hell of a thing to be saddled with. The clothes on your back and this enormous wooden clock.

I have nightmares about family albums burning up in a fire, because I have the gene that makes you a family archivist. Every family has one. I keep a list of all the surnames in my family going back five generations. I’ve visited the exact farms my ancestors left behind while emigrating to the new world. In the seventh grade I googled our family crest every night, and know the heraldry behind every cross and rose. I gifted DNA tests to my parents out of a rabid, self-interested curiosity (but refused the test myself because of concerns that China would purchase my genome and use it to cook up some hateful virus targeting bookish men of the West).

There is a compulsion to gather the facts. I think it’s rooted in an obsession with narrative. All my life, I have looked to the past for clues about myself. When I’m bored at work I look up tidbits about the careers of distant relatives — spies, diplomats, pilots, geologists — I think of how their proclivities affect my own work.

In photos especially I find this to be true. I once asked my mother if her children’s personalities were innate or had developed with time, and she replied that from the moment each of us were born — there we were. So there is an essence, from the beginning. It’s hard to care about photos of strangers in their youth. But photos of our lovers as children we find interesting precisely because we feel their essence is present in the photo, and therefore we can learn something about them. “Look, you still do that thing with your hands.” That is what drives my impulse to dig into family archives, it’s trying to piece together your essence from hints and scraps.

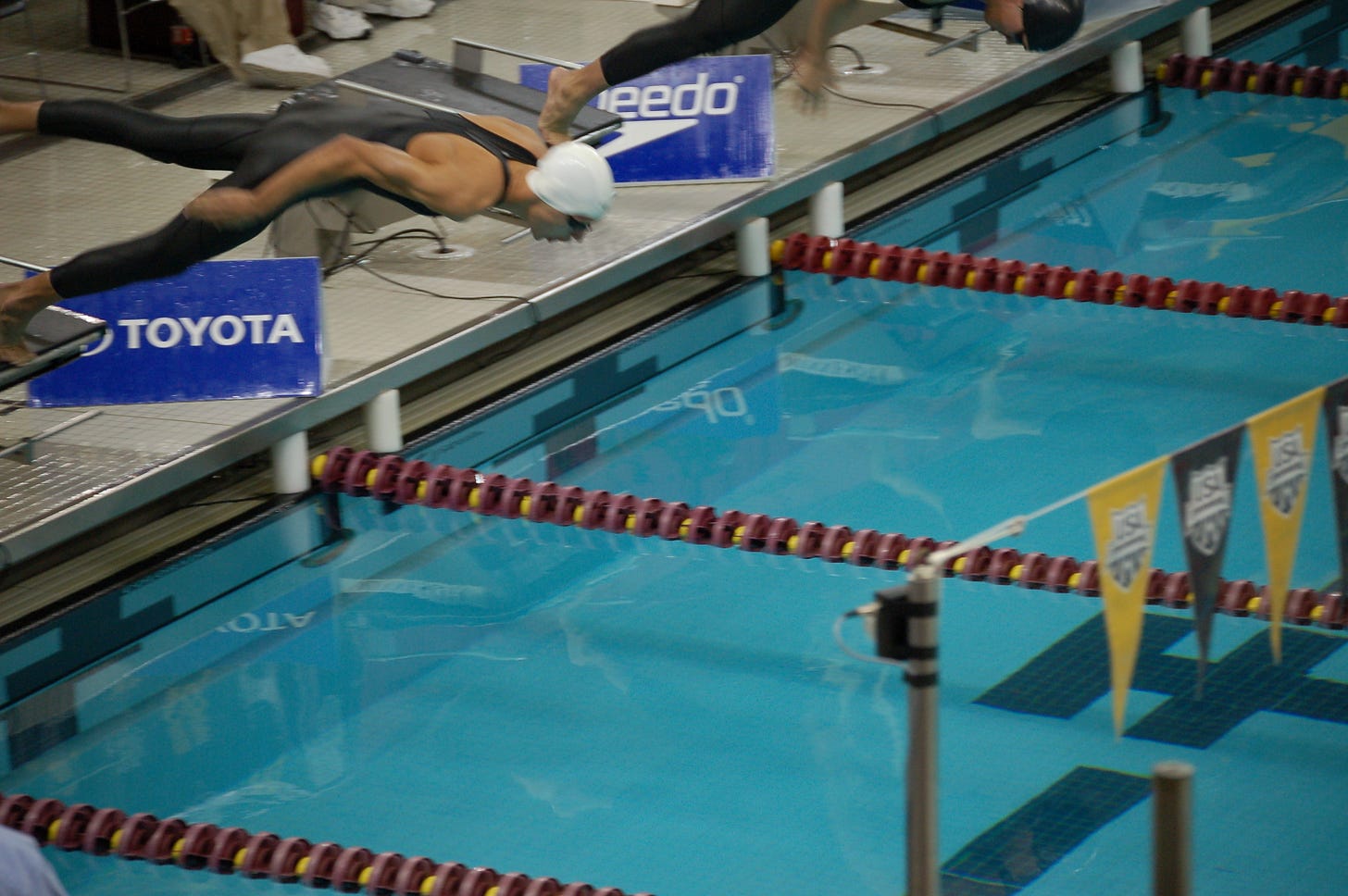

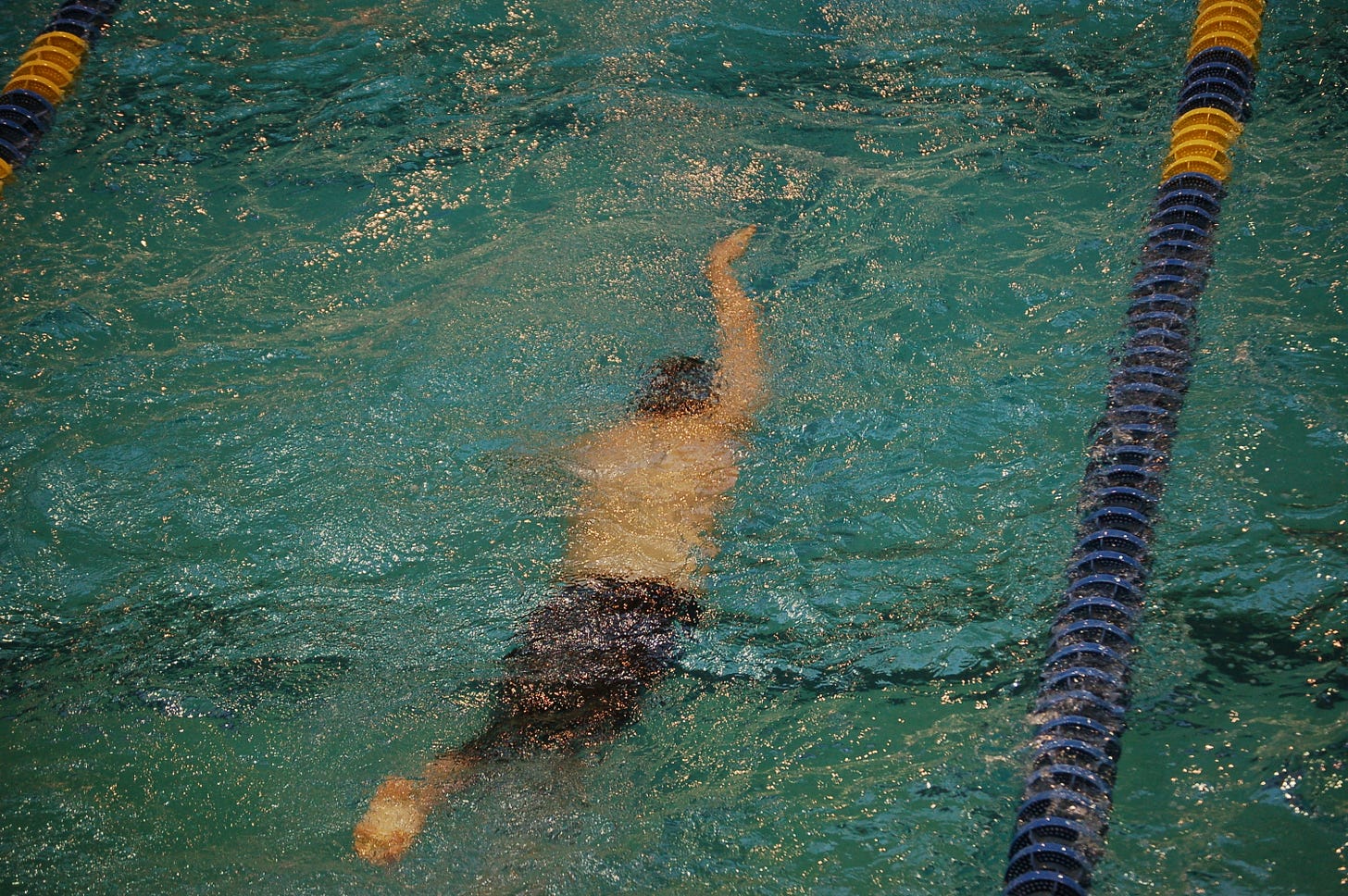

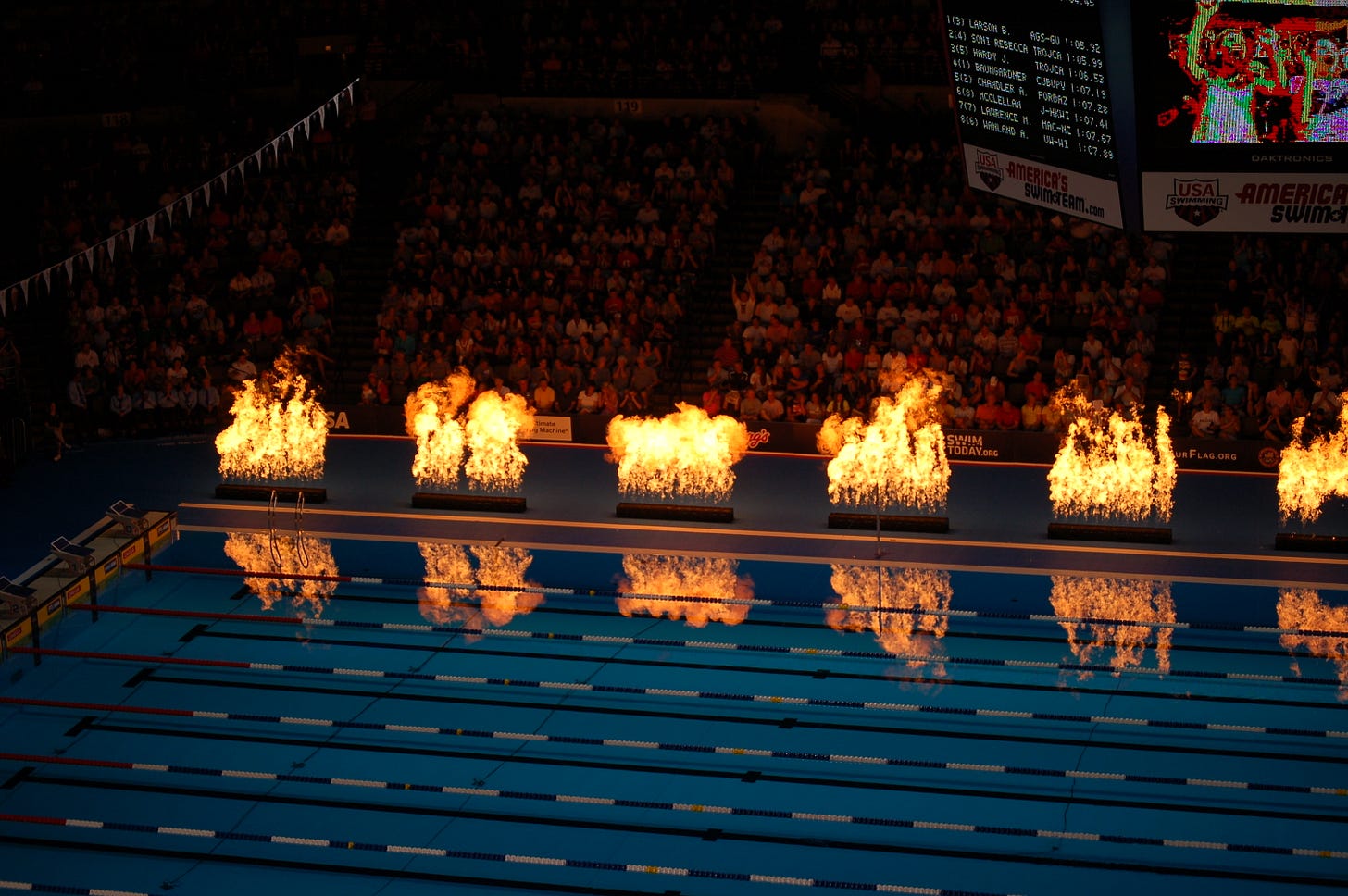

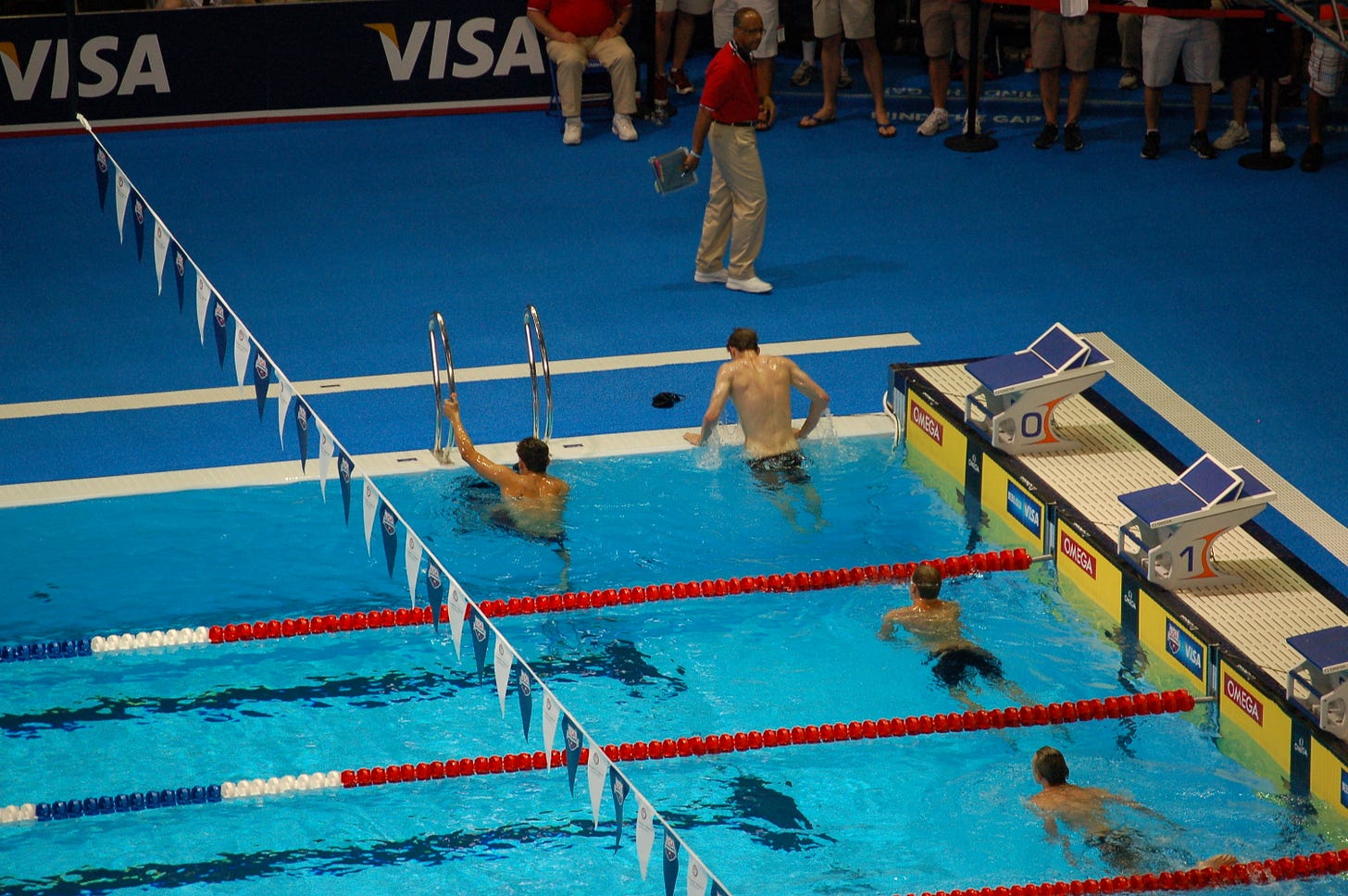

Happily, I was born into a family with strong documentary tendencies. In 2002, my father bought a DSLR camera. We took 30,000 photos with it over the next decade. Recently, fearing the ancient family computer going up in flames, I sorted through all our photos and uploaded the best ~1,000 to a family cloud account. While looking for “good” photos, I was charmed by certain “bad” photos, especially ones that had become anonymized through movement, distance, obliqueness, crowds, misplaced focus.

I like these photos because I am not in them. No one is. If I glance over them quickly, I get a feel for the texture of the time and country that I lived in. They are like photos on the wall of a stranger’s house.