“Praise, praise!” I croak. Praise God for all that’s holy, cold, and dark. — Frederick Beuchner

These days I am almost always cold. Call it winter but nonetheless it is intolerable.

I once went winter camping on the Minnesota-Canadian border. I was in the Boy Scouts, and if someone had been paid to devise a scenario to maximize my personal suffering, they couldn’t have done a thing different. We built a shelter on a frozen lake by hollowing out a pile of snow. Four of us slept inside, which sounds cozy, like foxes in a den, but the reality — the endless shivering, lying awake, thick ice beneath us and fish below the ice, someone quietly weeping in the dark — was like a prison camp.

Before bed I put on new socks and noticed that my toes had turned a curious shade of gray. Sixteen hours you’re supposed to lie in your sleeping bag and wait for the sun, but around midnight I got up to pee, and it was so bitter and bleak outside that I threw up. Wind chills fell to -27°. Now I know that hell is cold. In the morning, I was sent to base camp to be treated for frostbite, but first I spent another eight hours of darkness begging God to let me feel warmth again.

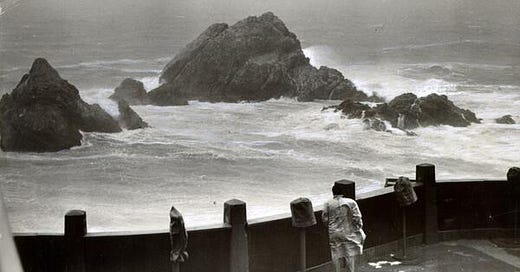

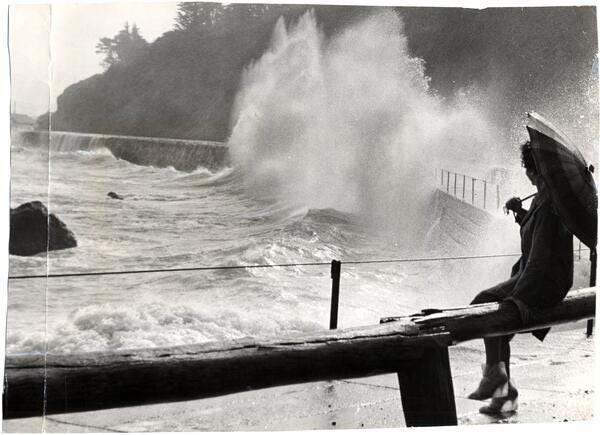

That was the coldest I’ve ever been. Second coldest was a picnic in San Francisco.

California cold is 44° and bone deep. Northern cold at least comes with ice and snow and those activities that exist in the winter regions of the mind: skiing, skating, Christmas carnivals. In California none of this exists, you just do the same things you were doing in the summer — running, cycling, picnicking — only now you’re wet and the wind is picking up.

I live in a Victorian house without any sort of heat. I have a marvelous sun well that brims with shadow and cold. My walls breed cold, something to do with thermal mass, and the cold just pours out of the wood. When I move through my apartment I drag my space heater with me, like a monk hauling a pan of coals around a crypt. And my single-pane windows are only the simulacra of a barrier between me and the outdoors, in fact I can often reach my hand right through them, because I keep several windows open at all times, even in the winter, as a result of certain ideas I developed about air flow, specifically a concern that if I didn’t have fresh air in my apartment at all times the carbon dioxide buildup would slowly drive me insane and eventually kill me, a theory I never bothered to test with any kind of meter or scientific research and only stopped worrying about recently when I went back to Minnesota and observed that most people live all winter long with their windows shut and seem fine or at the very least not insane or dead in statistically significant numbers.

Minnesota can teach you something about winter. Thanksgiving is a good opportunity to do some thinking about winter, to prepare oneself. Winter days with low clouds of very fine gray, and the trees all black. I found it strange this year that there were no birds. Yes, they’ve all gone south, I know how migration works, however it feels odd that the trees should be empty for so many months, with nothing up there except bare branches to knock together.

The effect of low clouds is to make the world seem small, which is the great secret of winter. On a clear night, you stand out in the mud with nothing between you and God and death above, which is the last thing anyone needs to feel in December. You have to shrink your sphere of control. The low, static ceiling of winter clouds circumscribes the universe, it says the known world is limited just to the neighborhood. You are not alone on a planet in the dark and empty firmament. You’re getting firewood from the backyard and admiring how blue the snow looks in the evening. Streetlights and string lights and lighted windows reflect off the clouds and light the world from within, a self-sufficient scene in which even the sun and the moon are deposed. At night, my mother closes the blinds over every window in the house, and though she says its to trap the heat in, really it’s about setting limits.

I suffer from a syndrome, disease, or phenomenon, it depends whom you ask, called Raynaud’s, an affliction of the blood vessels in the extremities, it’s not all that interesting or severe on the spectrum of phenomena you can suffer from, and the upshot is that when it’s cold outside all the blood runs out of my hands and feet, I lose sensation, and my digits turn a corpselike yellow. The phenomenon can be treated with simple lifestyle changes: keep warm, wear mittens, avoid caffeine, reduce stress, stop smoking. Nothing unreasonable. This year, I’m working on wearing mittens and not stressing.

Sitting in my ice-box apartment, waging war against the phenomenon, I will my body to produce heat. I think of how much effort and energy it takes to heat my apartment, and how quickly the heat is lost. It is one of the great miracles of the human form and a triumph of biology that we can sustain a 98.6° body temp in even the most intemperate wind, sleet, and snow, and furthermore it is no great surprise but indeed consequential that for millennia fevers have been a receiving state for holy visions. At the gym, I go to the steam room four times a week, sometimes more.

I would like to get better at generating heat, and for this reason among others I used to swim in the bay. Great shacks along the water host swimming clubs, and the regulars have developed thick layers of brown fat, like the harbor seals, and likewise they bark at my bloodless fingers and toes when I emerge from the lagoon. They are the happiest men and women I’ve ever met. Even Mao Zedong reportedly “had a genuine love for swimming . . . in the freezing river water during the winter as a form of physical training.” So I don’t doubt that cold water has its benefits, but for me in San Francisco it was a matter of going from cold to cold and never really warming up, so I stopped. Now my philosophy about cold is the same as my philosophy about suffering, which is that it can help one ascend but you cannot make me like it.

Saturday was the winter solstice. Last November, the end of daylight saving time came as a private calamity. I could not stop catastrophizing the loss of daylight, I had a bad feeling about the dark, as though the days would not stop getting shorter until there was only ancient, arctic night left. So the solstice was like a holy day and a great relief, with the days growing longer, and every extra minute of sunlight dragging behind it degrees of warmth. The dybbuk only passed in its entirety when I made my annual pilgrimage to the mountains for Christmas and, while walking home one night, saw two foxes playing in the snow under an iron lamp-post.

Certain images arrest you, and though there are not too many, one can draw upon them for strength for a long time after. They are tent poles in time, integral to the structure of the bounded universe. The foxes under the lamp were one of these. So I have since accepted winter as necessary conditions for such images. And the cold becomes almost bearable. Almost.

CONTENT CROP 🌾

Iain McGilchrist’s New Era || First Things

Many philosophers and physicists have argued against reductionism, or what McGilchrist calls the “school of nothing buttery”: the approach that dictates that everything can be accounted for in terms of its parts. Human behavior can be explained in terms of genes, complex systems in terms of physical particles. However forceful the philosophical arguments against reductionism, it exerts immense power over the contemporary mind, partly because it appears to be a complete worldview with an answer for every question. And therefore it can be finally displaced only by a worldview as comprehensive in scope and as detailed in application. That is why The Matter With Things has to be 1,579 pages long. Reductionism, in McGilchrist’s view, is like not getting the joke or not hearing the music: a failure to see properly.

note: I bought the book. will report back eventually

The Man Painting America’s Wars || The New Yorker

If you didn’t know that these were the sites of enormous violence, you would think they were simply a gazetteer of some of Earth’s most majestic landscapes.

note: can’t stop thinking about these landscapes

What was Psychiatric Deinstitutionalization? || Damage Mag

Others of them have changed location, or names. There was one called the Hartford Retreat, set up in Connecticut at a time when Hartford was a very affluent part of the country. That, now, is called the Institute of Living—an attempt, I think, to disguise what it's about. Unfortunately, its address is “Asylum Avenue, Hartford, Connecticut,” so it doesn't quite work.

note: the Marxists over at Damage Mag keep putting out reasonable analysis

THE BOOK BARN 📖

Balcony in the Forest by Julien Gracq

(Fiction, 1958. $15)

Frontier prowlers, idlers of the apocalypse, living without material cares on the brink of their sociable abyss, familiars of signs and presages, having no commerce save with a few cloudy and catastrophic grand incertitudes, as in those ancient watchtowers one comes upon at the sea's edge. And after all, Grange reminded himself, sinking deeper into his dream, that too would be a way of living.

note: good book if you like reading about people waiting for things to happen